Mathilda Tham was Visiting Professor in Fashion at Beckmans between 2007 and 2012, focusing on fashion and sustainability. Originally a fashion designer educated at the same school, she became a researcher out of frustration with the fashion system, dedicating herself to finding new ways to engage with fashion. In 2018, she co-founded The Union of Concerned Researchers in Fashion, a global network for radical transformation of the fashion industry which, in 2020, was followed by Earth Logic: Fashion Action Research Plan co-written with Kate Fletcher. In this text, she addresses future fashion activists with the concept of caring from fashion, a relational practice based on the conviction that fashion is a worthy matter of care and that designers need to increase their action space. “Fashion is beautiful and vibrant and can make us feel free. But it can also lock us in – in our bodies, our thoughts, our actions, how we perform as fashion people.”

I remember a book my mum presented my teenage self. It was called Twelve letters to Teena (my translation from Swedish Tolv brev till Tonina) and was already then dated.1 It included a chapter called “Is Gösta funny?” dealing with drinking, and fashion advice — never mix brown with blue. Yet, I appreciated the spirit of the gift and it turned out some of the pieces of advice held and if they didn’t at least made me realise that young women before me had had periods, sex worries, alcohol and drug dilemmas and fashion worries too. Alas, there was no chapter on being an activist from within fashion.

So, I offer this text as a letter to fashion designer activist teenagers or coming of agers of any age who grapple with caring from within fashion. I meet some of you when I teach, at degree shows, at conferences and when you do placements for one of my fashion designer friends. I see your work and hear you speak. I am amazed at you. So many things you are doing better than I did. You are outspoken feminists, some of you seem to accept your bodies in the shape they come, you find and make communities, some of you actually know “good enough” and refuse to work through the night. You know so, so much about the world. You are critical as well as creative, you voice acute questions, you are witty, you seem confident. Yet, at the end of my encounter with you, say at a lecture, you sometimes share your doubts and insecurities. You say “but still, what can I do, after all fashion is fashion, you know”. Once, I found one of you crying in the corridor at a conference, feeling ashamed after having shared vulnerabilities of being in fashion during a discussion. I meet emerging fashion activists of my own age too. Brilliant designers, with long and rich experience, who have traveled the world and seem to epitomize a successful creative career. Yet with a short embarrassed laugh you sometimes say you feel dissatisfied, uneasy, and that you would like to “do” something, often accompanied with “but, you know fashion is fashion after all”.

In this letter, I would like to explore how it can be possible to care from within the specific context of fashion. What are the possibilities of having a voice and making change as a fashion designer (or perhaps other fashion practitioner)? What are the resistances, pragmatically and paradigmatically? Fashion is beautiful and vibrant and can make us feel free. But it can also lock us in – our bodies, our thoughts, our actions, how we perform as fashion people. At the time of writing, science gives us but a decade to avert catastrophic climate change.2 Fashion’s role in environmental degradation is well established, as are priorities for change. Yet too little is happening too slowly. Therefore it is imperative to discuss how we can care from within fashion and how we can support each other to care.

Coming to Care

Over the years, I have had many ways of narrating my affiliation with fashion. First, when I had been accepted on the fashion programme at Beckmans College of Design, unequivocally jubilantly proudly loudly (hoping the people at the table along would hear as well): I’m going to become a fashion designer! Later, agonising: I can’t go on until I’ve reconciled my passion for fashion with the growing awareness I have of its tolls on people and environment. And then, keeping fashion far back on my list of affiliations as I realized that even a PhD, a professorship and active work to change fashion didn’t stop people from using my fashion affiliation to belittle me and reduce my power. And now, just the other day, I heard myself saying: I am glad and proud to be from fashion. I learnt anger and agency at the heart of sexism, ablebodyism, whiteism, ageism, lookism, growth centricism (please top up as you like). I learnt from one of the most polluting and excluding fields AND from the most fun, creative and dedicated people.

I can now see that this changing narrative manifests my feelings about fashion in relation to the world, and the degree of agency – ability and space to act – I have perceived, at different times, that I have. My shifting narrative partly reflects a process of increasing problematization of fashion in society, in turn reflecting a more general environmental awakening. When I started my fashion journey as a 21 year old student in 1991, fashion – although certainly regarded as frivolous and low on the hierarchy of knowledge making – was not widely considered the eco and people murderer it is today. So, as I started out, the fashion space I was allocated was big enough for me and I was content. As fashion grew for me, through my realization of its bad effects in the world, I no long felt my radius of action was sufficient. I left fashion. Then later, even though I was not exactly allocated more space, I was able to grow my knowledge and confidence enabling me to claim a larger fashion space for myself.

Care

Care is everything that is done to maintain, continue, repair, “the world” so that all can live in it as well as possible. 3

That world includes our bodies, our selves and our environment, all of which we seek, to interweave in a complex, life-sustaining web. 4

Maria Puig de la Bellacasa’s5 notion of care alludes to care being a relational practice which takes place within complex systems. This notion of care also points directly to the sustainability of our world. Environmental sustainability in relation to fashion has been my primary context of care, although this interplays with social, cultural and economic dimensions of sustainability. Design thinker John Thackara once wrote that there are three possible responses to the accusation that designers are trashing the planet: denial, (paralysing) guilt, or becoming part of the solution.6 From my experience rather than options, they are steps in a process of coming to care. Denial is a phase: “it can’t be true”, “I didn’t do nuffink”. Guilt is a phase: “I feel so bad about being part of this, I just want to hide”, “I can’t see a way out”. Action can be a long phase and a process of discovery of new ways of being and relating in the world. Coming to care in fashion means being able to take in “what’s wrong”, our own role in this, and then being able to find ways to do something about it. In my PhD research I found that these present vicious or virtuous cycles.7 An experience of agency, being able to do something, increases our openness to learning, to seeing our own role in problems and solutions, perceiving fashion and sustainability as compatible, and wanting to do more to change and to influence others. Conversely, without an experience of agency, we shut ourselves to information, we regard fashion and sustainability as incompatible and so forth. We could say that the experience of agency determines whether we are in a fashion bubble or in the world. This letter therefore goes on to explore agency in fashion.

Fashion ambivalence and conflict

Fashion is, in several ways, a space of conflict and also stages conflict and ambivalence. Fashion design is a “high status low status job” where fashion designers are simultaneously scolded and lauded.8 On the one hand fashion enjoys high status, is considered a creative, dynamic field. It is a highly lucrative industry, employing millions of people globally. High profile fashion shows are surrounded by exclusivity and glamour. On the other hand, designers in my study expressed a lack of trust and respect from the larger organization they worked in, and that the creative aspects of the work didn’t match their own expectations and that of society in terms of what fashion people should do. They were the targets of accusations of environmental and social degradation from media and from their personal networks. I have previously written about fashion as epitomizing general bulimic tendencies in society, fashion as a societal depository of shame9 and how fashion and sustainability is constructed as a paradox10 based on limited readings of both fashion and sustainability.11 12 13

Fashion has rarely enjoyed a very good reputation. Despite its undeniable success as a social and commercial phenomenon, it remains the very exemplum of superficiality, frivolity and vanity… It is the very personification of the individual alienated in the rush of consumption, of the self lost in the brilliant world of commodities.14

Barbara Vinken has described a series of societal objections to fashion dating back to the Old Testament and comprising moral (it’s debauched), political (it belongs to the aristocracy), gender (it’s the domain of women or homosexual men) and environmental arguments to reject it.15 Kate Fletcher and I coined the term “the fashion smirk” to describe the experience of being looked down upon by people considering themselves of more worthy fields.16

Mapping the Fashion Bubble and Agency

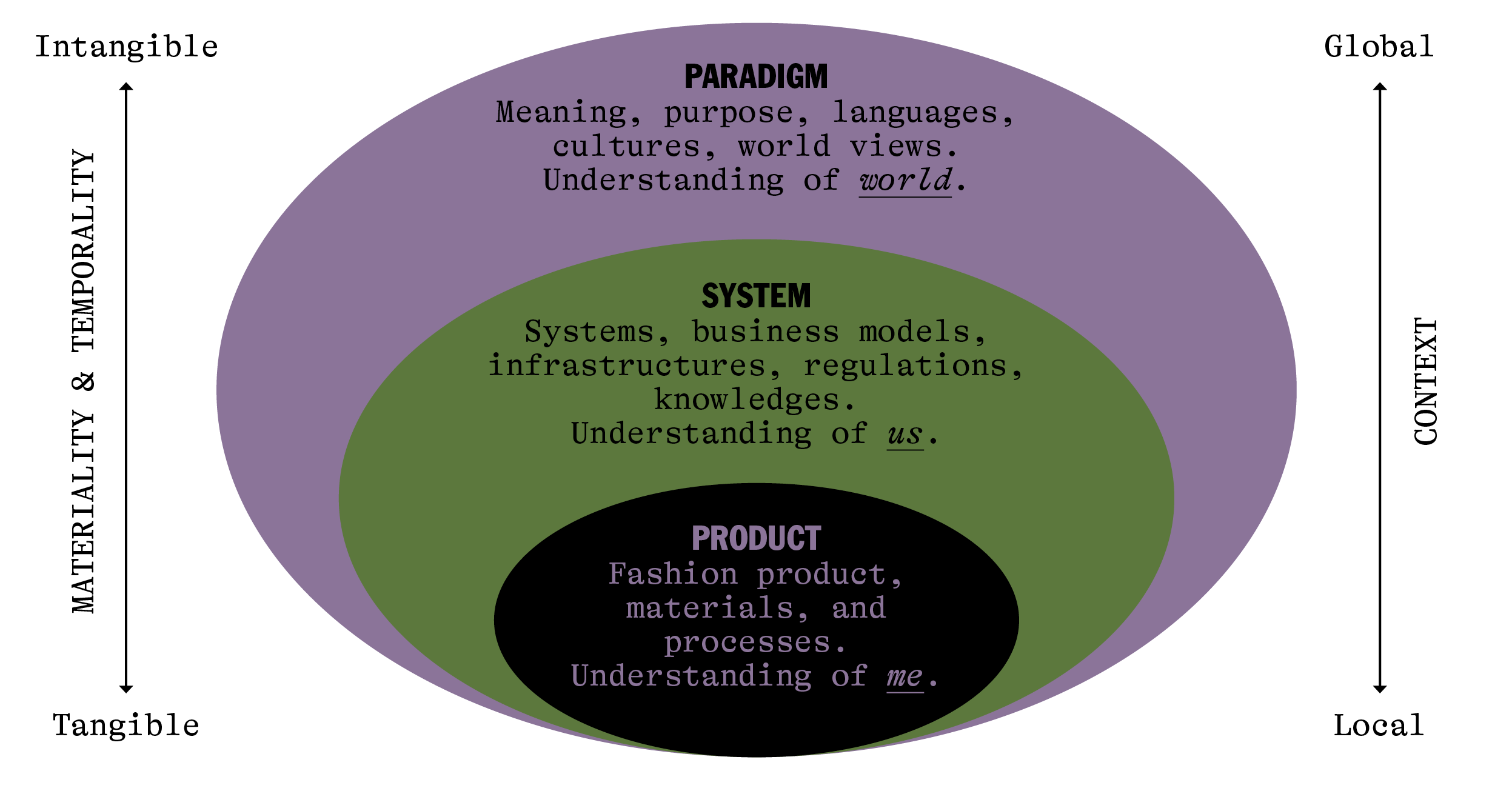

Fashion designers’ agency is limited in several ways. Imagine a fashion bubble nested in a larger world. There are forces both from within fashion – inside the bubble – and from outside it affecting the experience of agency of fashion people. The model comes from metadesign, meaning design of seeds for change and overarching design.17 It describes nested levels of products, systems and paradigm.18

Fashion bubble in the world.19

If we start at the inner layer, we find the fashion products, and the tools, practices, processes and technologies the fashion designer uses. Most budding fashion designers probably place their work and identity here. Fashion design creates artefacts. It is therefore at this level designers expect to and are expected to apply their creativity. The organization of a company, its briefs and those of fashion education also mostly confine design creativity to this level. The metadesign bubble model also traces generations of approaches to sustainability in fashion. The first generation targeted the products and processes solely, such as reducing chemicals or replacing conventionally farmed cotton with organic cotton. Confining the fashion designers’ role to the product level also limits their agency to this level.

Even if fashion designers’ work is mostly confined to the product level, the garments are dependent on systems and infrastructures, such as global production chains, and the fashion designer has to collaborate with people in a larger team, directly and indirectly interplaying with production, management, sales and marketing, as well as taking in zeitgeist, global events. Designers are of course aware of the systems fashion rely upon, including overproduction and overconsumption. Therefore, even if designers are able to specify less harmful materials and processes, this may not feel entirely satisfying if they are not also able to influence the larger system. A second generation of approaches to sustainability has started addressing fashion more systemically, for example by increasing infrastructure for reuse and recycle and even creating new business models, such as for renting fashion.20 Typically, only designers working for themselves or in small organisations are involved at this systemic level. The awareness of the wider map, despite our agency being confined to a small part of it, can cause a “cognitive dissonance”21 where different knowledges, thoughts and actions, and values at home (perhaps we try to eat organic food) and at work clash.

At the level of the system, we find ways of organizing fashion. The dominant fashion model is also a dominant barrier to caring in fashion. The fast fashion model is founded on the ability to separate gain from pain through geographical distance between takers and makers, placing cost on vulnerable communities and natural resources, and placing cost on future generations. The fast fashion model (as the name suggests) also means designers have to work really fast, making reflection time scarce. This can be read as a strategy to avoid dissent. It is hard to care without space to think and feel. The fast fashion model has become axiomatic, too big to fail, so all-encompassing it appears impossible to change. As critique of this system is becoming more ubiquitous, the walls around this fiction of inexhaustible resources are also hardening. This can be exemplified by how in a recent statement H&M’s former CEO Karl-Johan Persson warned of “terrible social consequences” if fast fashion is abandoned.22

The third level is the paradigm. This concerns how we understand the world, the meaning and purpose we attribute to it and us being here. It concerns culture and language, beliefs and norms. Paradigms are the water we swim in and the air we breathe, it can be difficult to discern them within our lifetime. Thomas Kuhn who coined the term paradigm shift described how the dominant paradigm suppresses ideas that jar with it, and that when a problem arises that cannot be solved within the current paradigm, it is deemed impossible to solve or a new paradigm emerges which is able to grapple with the problem, a paradigm shift. Kuhn stated that it is not possible to solve a problem within the paradigm which created it.23 The dominant paradigm or grand narrative that is guiding fashion and society more generally, is that of the economic growth logic. A third generation of approaches to sustainability in fashion is revisiting the purpose and meaning of fashion and explores how positive fashion experiences can be part of our lives in entirely new or new old ways. 24 25 26 27 Such comprehensive approaches engage directly with detrimental metanarratives such as that of inexhaustible natural resources, and therefore are needed to avert catastrophic climate change and take a route of “Great Transition” rather than “Conventional Development”.28 For fashion designers, without access to the full range of this map it is very hard or impossible to genuinely perform care.

In conclusion, fashion designers’ experience of agency is limited in several ways. The fashion bubble is upheld from inside, by the product level focus of the fashion designer role. Arguably, certain constructions of fashion also limit agency. They include notions of the lone genius (inherited from fine arts), and not conducive to the collaboration necessary for care – a relational practice. The construct or brand of fashion with a narrative of danger, exclusion and violence, coolness and blankness also limits agency. It doesn’t promote risk taking where we might show ourselves vulnerable. The pursuit of perfection and the experience of being on a stage, can make us rigid and tight – not an ally to the openness, fluidity needed to take in, empathise, collaborate, reaching out needed for caring. Importantly, the above are, for various reasons long held constructs of fashion and the fashion designer. The constructs interplay with, and reciprocally enforce the organization and system of fashion. For example, so long as design knowing is low on epistemological hierarchies (that is what kind of knowledge that is valued), fashion designers will not be given strategic roles, and thus keep performing product level work. It is true that in the past couple of decades, the best fashion education has been reformed by the introduction of contextual studies and critical thinking, arguably increasing designers’ thought space. Yet, designers’ action space has not been correspondingly increased. There is an asymmetry of awareness and voice. Can we see ourselves as people who are change makers? These constructions of fashion, from within the bubble, from outside and in collaboration, are probably the most damning for an agency to care. Pairing fashion with care though, I believe can take us further into an important exploration than the pairing of fashion with sustainability, as sustainability has suggested technical and specialist responses. Speaking of care and caring softens the edges as caring is practice done by a person – and indeed, almost anyone can care and does care about something at some point. Here are four key points for fashion and care.

“It is true that in the past couple of decades, the best fashion education has been reformed by the introduction of contextual studies and critical thinking, arguably increasing designers’ thought space. Yet, designers’ action space has not been correspondingly increased.”

1. Make Your Fashion Space

The importance of making your own space for creative and intellectual activity was evoked in Virginia Woolf’s legendary feminist essay A Room of One’s Own.29 For me, it has been liberating to understand design as nested levels of products, systems and even paradigms as in the map. I am free to dance between these levels, designing a thing, a process, a ritual, or a language. Paramount to my ability to care from within fashion, has been the creation of this space for myself. I’m no longer locked in the product, the associated materials and processes, the production methods. I can stretch. Your space will of course criss-cross different landscapes. The important thing is that you have the license to take and make the fashion space you need to experience agency.

“The important thing is that you have the license to take and make the fashion space you need to experience agency.”

2. Define Fashion

Central to growing your fashion space is defining fashion. Languaging works co-creatively with actions and perceptions, meaning that, for example, describing fashion and sustainability as paradox, will make it more likely that it is and continues to be.30 Language draws lines, opening or closing our imagination, action and thought space. Fashion is notoriously broad in characterization.31 Predominantly though, the commercial remit and the economic growth logic bracket it. However, as we know, the current business models are but a recent occurrence in fashion’s long history. Your definitions of fashion can break this, and other bubbles. You can choose it’s alliances, breaking patriarchical, colonial, human exceptionalist patterns. Perhaps most agentic might be defining fashion as a verb rather than a noun. What does your fashion do? What does it take to do it? Who do you do it with and where? What are the qualities and temporalities involved? Defining fashion also means defining creativity. Can you stretch it beyond the product level? Can you find creative satisfaction without (much) material throughput? Can you find it in team work and work spanning longer time periods?

3. Collaborate

Growing your fashion space does not have to mean leaving the fashion garment, instead you can grow by making stronger relationships with others in the organization, in society, global communities of human and more than human species, getting involved in how fibers are grown, with a user community, exploring how the clothes you design are worn and can be mended. This means stretching your fashion space to more stages of the fashion lifecycle and to more of its stakeholders. Often, this is easier from a smaller organization, rooted in a local community, but everywhere and anywhere there is scope for some collaboration and care is a relational practice.

4. Practice Making a Fuss

In our professional and personal lives, we perform roles and there are societal norms and expectations for how to perform these roles too. I have noticed that transcending these norms and expectations (also walls of a bubble), causes much resistance. There are also implicit rules for which rules that can be broken and how. For example, fashion loves its enfants terribles. When we transgress established boundaries, resistance is staged both by people around us, and by ourselves. For most of us, it is uncomfortable to perform outside norms and expectations. When we start breaking the order it can cause unease, disappointment and anger in others.

The journey from being a “good girl” to making people very angry has not been easy for me. In the beginning I was shocked. I thought people would be happy when I “offered” sustainability to them. Instead I was met with ridicule, avoidance, irritation and anger. It is unpleasant to be made to feel you are a party pooper. Suddenly, you, rather than, for example, environmental degradation, is the problem. Sara Ahmed brilliantly discusses how you become a problem when you in fact are describing a problem as a facet of activism and the figure of the “feminist killjoy” in her book Living a Feminist Life.32 It is hard not to feel liked and to meet conflict. Yet, for change to take place, we have to, in Stengers and Despret’s terms, which come from a feminist perspective be “women who make a fuss”.33 I have learnt that certain combinations of fuss making are especially provocative, such as challenging environmentally harmful practices, questioning the growth logic AND being a feminist. When you add knowing in unconventional ways (such as through artistic practice), resistance can be almost devastating. Sometimes I have thought perhaps I should add just a touch of witchcraft to make the picture complete. Certain clusters of ideas seem to be addressed with an armour of a much longer history than my attempts at change making.

Courage

A fashion friend of mine, working for a directional fashion brand, made the observation that many fashion people (including herself) accept working hours and some other conditions breaching or bordering on breaching human rights because of low self-confidence. It does take confidence to develop a voice and speak up and out. The space to develop your voice is curtailed if you belong to a minority, as bell hooks has articulated in relation to women, race and class.34 It is important to recognize that fashion designers, albeit privileged in many ways, are minority knowers in relation to knowers affiliated with, for example, dominant natural scientific frameworks. This knowledge bias interplays with the gender bias. It is important to know that such resistance is structural (just like sexism and racism) so that we don’t take it personally. Nowadays, I am (mostly) able to read the resistance I get as confirmation that my work is important. Such “itches” are leads to where to probe and push. Making a fuss like most other things, takes practice. Growing our comfort zone around fuss making should be part of any fashion education and also workplace. There are tools we can acquire to manage conflicts. The principles of Nonviolent Communication have been helpful in my exploration of how to initiate dialogue and collaboration in my fuss making.35 With making a fuss, again, comes need for collaboration. We need a community of allies for support. Obviously, through collaboration our change making will also be more powerful.

“Making a fuss like most other things, takes practice. Growing our comfort zone around fuss making should be part of any fashion education and also workplace.”

Growing the fashion space can be challenging and challenges. Many systems uphold what a dominant understanding of fashion is today. Fashion education, fashion media, fashion companies. Yet, these systems are all made by people, which means they can be unmade and new systems made. The space is so important. As a woman and as a fashion person I have often accepted a very small space for myself, my body, my thoughts, my actions. We need to get out of this bubble to care as fashion people. Let’s leave the straight jacket, the lily foot shoes. Let’s turn the fashion bubble upside down, and like in the snow globe make a storm of all the precious glitter. We might ask, but what is left then of fashion. Puig de la Bellacasa’s notion of care also comprises matters of care.36 Fashion is a worthy matter of care, and we do care about fashion. Let’s trust that our care can make fashion grow and blossom, breaking norms, rules, making new fashion spaces.

Endnotes

- I. Granlund, Tolv brev till Tonina, Stockholm, Natur & Kultur, 1957.▴

- IPPC, Global warming of 1.5C, Switzerland, IPCC, 2018.▴

- M. Puig de la Bellacasa, Matters of Care: Speculative Ethics in More than Human Worlds (3rd ed.), Minneapolis, MN, University of Minnesota Press, 2017, p. 161.; J.C. Tronto, Moral boundaries: a political argument for an ethic of care, New York, Routledge, 1993. ▴

- M. Puig de la Bellacasa, Matters of Care: Speculative Ethics in More than Human Worlds (3rd ed.), Minneapolis, MN, University of Minnesota Press, 2017, p. 3.; J.C. Tronto, Moral boundaries: a political argument for an ethic of care, New York, Routledge, 1993. ▴

- Puig de la Bellacasa, Matters of Care: Speculative Ethics in More than Human Worlds. ▴

- J. Thackara, Foreword, in J. Chapman and N. Gant (eds.) Designers, Visionaries and Other Stories: A Collection of Sustainable Design Essays, London and Sterling, VA, Earthscan, 2007. ▴

- M. Tham, Lucky People Forecast: A Systemic Futures Perspective on Fashion and Sustainability, PhD thesis, Goldsmiths, University of London, 2008. ▴

- Tham, Lucky People Forecast: A systemic Futures Perspective on Fashion and Sustainability. ▴

- M. Tham, The Green Shades of Shame, Vestoj – The Journal of Sartorial Matters, Issue 3, 2012.▴

- See e.g. S. Black, Eco-chic: The fashion paradox, London, Black Dog Publishing, 2008. ▴

- Tham, Lucky People Forecast: A Systemic Futures Perspective on Fashion and Sustainability. ▴

- M. Tham, Languaging fashion and sustainability – towards synergistic modes of thinking, wording, visualising and doing fashion and sustainability, The Nordic Textile Journal, Special Issue Fashion Communication, 1, 2010.▴

- M. Tham, Integrating fashion and sustainability – how might futures approaches to change transcend a current paradigm of thinking, doing and communicating fashion? Dare Magazin für Kunst und Überdies, Apocalypse Green Issue, 2011. ▴

- B. Vinken, Fashion Zeitgeist: Trends and cycles in the fashion system, Oxford, Berg, 2005, p.3. ▴

- Vinken, Fashion Zeitgeist: Trends and cycles in the fashion system. ▴

- Tham, Lucky People Forecast: A Systemic Futures Perspective on Fashion and Sustainability. ▴

- J. Wood, Design for Micro-utopias: Making the Unthinkable Possible, Design for Social Responsibility, London, Ashgate, 2007 ▴

- M. Tham, BOOST metadesign, in Tham, M., Ståhl, Å. and Hyltén-Cavallius, S. Oikology – Home Ecologics, Växjö, Linnaeus University Press, 2019. ▴

- M. Tham, BOOST metadesign; after A. Lundebye, 2004, Senseness, MA thesis, Goldsmiths, University of London.▴

- Mistra Future Fashion, Research for systemic change in fashion via closed loops and changed mindsets. www.mistrafuturefashion.com, 2019, (accessed 15 July 2019). ▴

- L. Festinger, A theory of cognitive dissonance, Stanford, CA, Stanford University Press, 1957. ▴

- H. Hoikkala. H&M boss warns of ‘terrible social consequences’ if people ditch fast fashion, 2019, www.independent.co.uk/[…], (accessed 11 November 2019). ▴

- T. Kuhn, The structure of scientific revolutions, Chicago, IL, University of Chicago Press, 1962.▴

- K. Fletcher and M. Tham, (eds.) Routledge Handbook for Sustainability and Fashion, London, Routledge, 2014.▴

- K. Fletcher, Craft of Use: Post-Growth Fashion, London, Routledge, 2016.▴

- T. Rissanen and H. McQuillan, Zero Waste Fashion Design, Bloomsbury, London, 2016.▴

- A. Twigger Holroyd, Folk Fashion, London and New York, I.B. Taurus, 2017.▴

- M.D. Gerst et al., Contours of a Resilient Global Future. Sustainability 2014, 6, 2014, p. 127.▴

- V. Woolf, A Room of One’s Own, London, Hogarth Press, 1935 [1929].▴

- Tham, Languaging fashion and sustainability – towards synergistic modes of thinking, wording, visualising and doing fashion and sustainability, after H. Maturana and F.J. Varela, The tree of knowledge: The biological roots of human understanding, Boston, New Science Library, 1987.▴

- G. Sundberg, Mode Svea: En genomlysning av området svensk modedesign, Stockholm, Rådet för arkitektur, form och design, 2006.▴

- S. Ahmed, Living a Feminist Life, Durham and London, Duke University Press, 2017.▴

- I. Stengers and V. Despret, Women Who Make a Fuss: The Unfaithful Daughters of Virginia Woolf, Univocal Publishing, 2014.▴

- b. hooks, Feminism is for Everybody: Passionate Politics, Cambridge, MA, South End Press, 2000.▴

- M. Rosenberg, Nonviolent Communication – A Language of Life, Encinitas, CA, Puddledancer Press, 2015.▴

- Puig de la Bellacasa, Matters of Care: Speculative Ethics in More than Human Worlds▴

References

- Ahmed, S. Living a Feminist Life. Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2017.

- Black, B. Eco-chic: The Fashion Paradox. London: Black Dog Publishing, 2008.

- Festinger, L. A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1957.

- Fletcher, K. Craft of Use: Post-Growth Fashion. London: Routledge, 2016.

- Fletcher, K. and Tham, M., (eds.). Routledge Handbook for Sustainability and Fashion. London: Routledge, 2014.

- Gerst, M.D. et al. Contours of a Resilient Global Future. Sustainability 2014, 6, 2014, pp. 123-135.

- Granlund, I. Tolv brev till Tonina. Stockholm: Natur & Kultur, 1957.

- Hoikkala, H. H&M boss warns of ‘terrible social consequences’ if people ditch fast fashion. 2019. www.independent.co.uk/news/business/news/hm-fast-fashion-boss-karl-johan-persson-environmental-damage-a9174121.html (accessed 11 November 2019).

- hooks, b. Feminism is for Everybody: Passionate Politics. Cambridge, MA: South End Press, 2000.

- IPPC. Global warming of 1.5C. Switzerland, IPCC, 2018.

- Kuhn, T. The structure of scientific revolutions. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1962.

- Lundebye, A. Senseness. MA thesis. Goldsmiths, University of London, 2004.

- Maturana H. and Varela, F.J. The tree of knowledge: The biological roots of human understanding. Boston: New Science Library, 1987.

- Mistra Future Fashion. Research for systemic change in fashion via closed loops and changed mindsets. 2019. http://mistrafuturefashion.com (accessed 15 July 2019).

- Puig de la Bellacasa, M. Matters of Care: Speculative Ethics in More than Human Worlds (3rd ed.). Minneapolis MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2017.

- Rissanen, T. and McQuillan, H. Zero Waste Fashion Design. London: Bloomsbury, 2016.

- Rosenberg, M. Nonviolent Communication – A Language of Life. Encinitas, CA: Puddledancer Press, 2015.

- Stengers, I. and Despret, V. Women Who Make a Fuss: The Unfaithful Daughters of Virginia Woolf. Univocal Publishing, 2014.

- Sundberg, G. Mode Svea: En genomlysning av området svensk modedesign. Stockholm: Rådet för arkitektur, form och design, 2006.

- Thackara, J. Foreword. In J. Chapman and N. Gant (eds.), Designers, Visionaries and Other Stories: A Collection of Sustainable Design Essays. London and Sterling, VA: Earthscan, 2007.

- Tham, M. Lucky People Forecast: A Systemic Futures Perspective on Fashion and Sustainability. PhD thesis. Goldsmiths, University of London, 2008.

- Tham, M. Languaging fashion and sustainability – towards synergistic modes of thinking, wording, visualising and doing fashion and sustainability. The Nordic Textile Journal, Special Issue Fashion Communication. 1, 2010, pp. 14–23

- Tham, M. Integrating fashion and sustainability – how might futures approaches to change transcend a current paradigm of thinking, doing and communicating fashion? Dare Magazin für Kunst und Überdies, Apocalypse Green Issue. 2011, pp. 50–56.

- Tham, M. The Green Shades of Shame. Vestoj – The Journal of Sartorial Matters. Issue 3, 2012.

- Tham, M. BOOST metadesign. In Tham, M., Ståhl, Å. and Hyltén-Cavallius, S. Oikology – Home Ecologics. Växjö: Linnaeus University Press, 2019.

- Tronto, J.C. Moral boundaries: a political argument for an ethic of care. New York: Routledge, 1993.

- Twigger Holroyd, A. Folk Fashion. London and New York: I.B. Taurus, 2017.

- Vinken, B. Fashion Zeitgeist: Trends and cycles in the fashion system. Oxford: Berg, 2005.

- Wood, J. Design for Micro-utopias: Making the Unthinkable Possible, Design for Social Responsibility. London: Ashgate, 2007.

- Woolf, V. A Room of One’s Own. London: Hogarth Press, 1935 [1929].

Mathilda Tham’s work sits in a feminist, activist, creative space between fashion and design, futures studies and sustainability. Mathilda Tham is co-founder of Union of Concerned Researchers in Fashion, a global network for radical transformation of fashion. She is Professor of Design at Linnaeus University and also affiliated with Goldsmiths, University of London. She was visiting Professor in Fashion at Beckmans College of Design between 2007 and 2012. Publications include Routledge Handbook of Sustainability and Fashion, co-edited with Kate Fletcher.